From Small Beginnings... a true story

It all started with a single email…

Many years back, on the Independence Day of India on August 15, 1991, an Indian physics graduate student at the University of Maryland sat down on his computer and sent out a mail to some of his friends on the newsgroup.

Ravi Kuchimanchi had attended many public rallies and discussion meetings in and around his campus during those times about issues related to India – Kashmir, poverty, development, social justice etc. What he found frustrating was that beyond the discussions and slogans nothing much really happened. No actionable agenda!

So, he decided to bring action into the intents, and sent this mail with the subject line “Village Education Project”. As he wrote about a decade later, it was just a simple small idea:

“If we contribute $10 a month each we could take a village in India where there was no school, and find someone who would be willing to teach there if we paid a small stipend. The challenge was to identify a village and a motivated teacher, make an appropriate syllabus and talk to the village children and inspire them to come to classes. Would anyone be interested?”

To his surprise, many responded. Some with commitment to donate, some with offer to identify such villages and garner support of the local community – one even wrote: “If you are starting an organization, I can help keep the accounts.”

Soon this group of friends started meeting regularly to discuss their plans. These discussions further refined and enlarged the scope of their work beyond only the school project. They realized that social problems do not exist in isolation, but are layered and interrelated. Rural education, for instance, is also nested in issues such as gender and caste relations, availability of human resources and infrastructure, livelihoods opportunities, etc. On the other hand, issues of gender and caste relations also have implications for maternal health, women empowerment, social justice, community governance, etc.

Such discussions brought greater clarity to what their approach to development needs to be. If social problems are interrelated, then solutions cannot be piecemeal and isolated from each other. Rather, they should have an integrated and holistic approach to address all village-level issues (education, health, agriculture, gender, governance, ecology, social justice, etc.), and work with the involvement and ownership of the local community. Only then they will be able to achieve their aim of “creating a sustainable, peaceful and just community.”

As more and more people started promising to donate money for the cause, they also realized the need of a bank account. One day, Ravi and two other volunteers drove to the local bank ready to open an account for the non-profit organization that they were starting. Except that they had not thought of what the organization will be called!

Some years later, he wrote about it, as they waited in the bank:

“…what shall we name our organization? Every 5 minutes we were excited about a different name. Finally, when the teller called us, we still didn’t have a name. We filled out the rest of the form and we were thinking desperately — the words like India, Progress and Development we thought should be there for obvious reasons, but what other words can we have so that the entire acronym itself would mean something. I asked the teller how she knew that this would be an account for a non-profit organization rather than something else — I was still foggy about the rules. She said “oh such accounts normally have the words like ‘association’ in them”… and she asked “you mean you don’t know what your organization is called??”….. I said, “Oh! we are the Association for India’s Development …. AID” and she approved the form and smiled, “good luck, it seems like a wonderful cause!”

And that is how the Association for India’s Development got established with a name and identity!

***

As more projects got identified and implemented, the need for more volunteers and funds became apparent. In 1994, to widen the involvement beyond the group of friends, Ravi and his housemate, Ramani Hariharan, came up with the idea of “Community Service Hour” (CSH). – one hour every Saturday, in a room in the Physics Dept of the University, which was open for anyone willing to volunteer to work on AID’s work.

Another innovative outreach initiative was to use the platform provided by the Independence Day and Diwali celebrations organized by the Indian diaspora. AID volunteers started using these celebrations through their cultural program “India Beckons” to put up plays and dances which highlighted the social problems in India and the projects being undertaken through AID.

Soon more volunteers started joining the CSH group. And they would bring others with them for the next meetings. People from diverse backgrounds, some even driving from other states to attend the CSH meetings. As Ravi recalled in AID’s newsletter, Dishaa (which was started by another volunteer) a few years later:

“What started as a group of science and engineering students soon transformed into a group of 30. A psychiatrist, a doctor, a professor of physics, World Bank employees, economics students, a minister from the Embassy, a priest, a car mechanic, social workers, visiting from India… began to frequent the CHS. Many became regular attendees… In the broad fields of projects, funds and awareness, the people in the CHS began to figure out what to do themselves.”

This diverse group of volunteers brought with themselves not just financial but also technical expertise to support AID projects.

Some volunteers who moved to (or came from) other cities opened AID chapters in their own locations. Thus, creating a decentralize network of autonomous AID chapters – a kind of people’s movement - each responsible of their own projects, fund raising and utilization.

Over time, AID had a volunteer strength of about 1000, about 40 chapters in USA, 10 supporting ones in India – and smaller ones UK, Canada, Australia etc. At any point of time, AID was (and is) supporting close to 100 projects in India both financially, and through technical expertise.

When in 2011, AID received the Times of India’s Social Impact Award (for “Global Contribution to India”) the newspaper described its activities as

“…a staggering sweep of projects within the country. From helping organic farmers in the Sunderbans, to teaching underprivileged kids in Tamil Nadu, from encouraging citizens to file RTIs to funding NGOs that fight corruption, from waste management in Bangalore to offering flood relief in Murshidabad, it is involved in diverse activities.”

***

In 1998, AID established its physical presence in India when Ravi and two others moved back to India to work full time on development issues and projects:

Balaji Sampath, a doctoral student from University of Maryland, who became actively involved in AID when his housemates brought him to the 2nd CSH meeting in 1994. He had played a pivotal role in spreading AID’s network in USA through his e-writings and visiting different cities and chapters to make presentation about AID’s approach to development.

Aravinda Pillalamarri, a Masters in South Asian Studies from the University of Wisconsin, had got associated with AID in 1995, when her parents had attended AID’s “India Beckons” cultural program, and had encouraged her to attend their meetings. Her earlier experience of living in a remote Indian village for six months, and her interest in people’s movement, sparked her interest to start working full-time with AID. Later she and Ravi also got married.

Many other AID volunteers too had started moving back to India, and there was a need to channelize their energies and an opportunity for closer collaboration with groups in India. Thus, AID-India, modeled on AID of USA, got established in 1998.

AID-India completed its 25th year earlier this week – which was also the nudge for me to document this story written in real-life by people to show that such stories are possible… and that there is a need to document and share them…

***

Post-Script/ Addendum – The Bilgaon Project

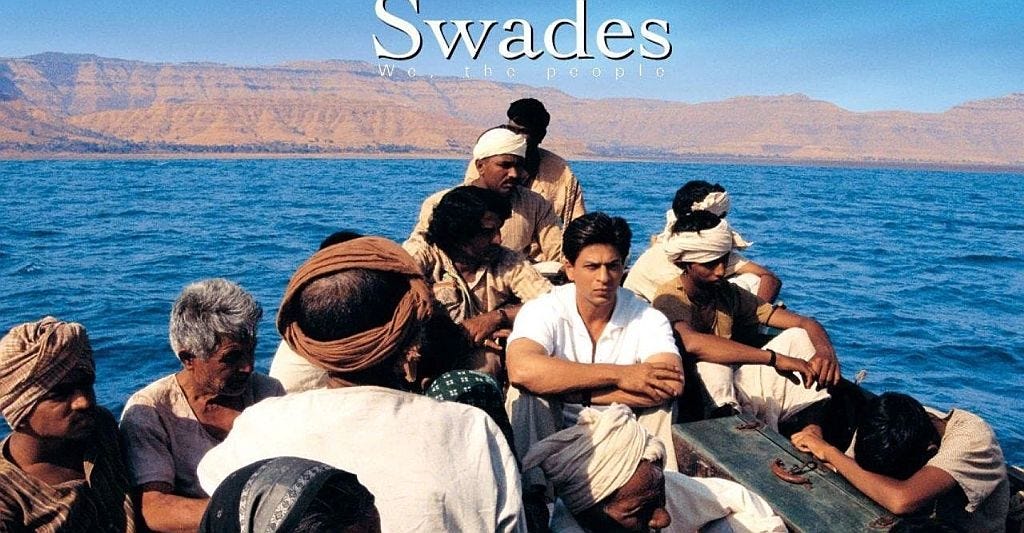

The story of AID would be incomplete without also narrating its Bollywood connection to the film, Swades. The story of the NRI Mohan Bhargava (played by Shahrukh Khan) who returns to India, accidentally lands up in a remote village (with no electricity, plenty of illiteracy, and backwardness), and uses his engineering and organizing skills to help the villagers build a micro-hydel plant to bring electricity to the village…

On return, Ravi and Aravinda decided to work on grassroot projects related to people’s movement, creating solutions for the poor through appropriate technology, advocacy, etc… or as Aravinda described in an interview, through Sangharsh (challenging injustice), nirmaan (creating alternatives/ solutions) and seva (responsible living/ service).

They were active participants in the Narmada Bachao Andolan, and that is how they came to Bilgaon, a small tribal region in Maharashtra located on a tributary of Narmada river, Udai. It consisted of 12 hamlets (about 180 families), scattered over a distance of 4km, had never seen electricity and, despite the mega-hydel project on the Sardar Sarovar Dam, had no hope of getting connected to the national grid.

But the region had a 10-meter waterfall from the tributary, and provided an opportunity to harness that energy to generate electricity for the village.

The work on the Bilgaon Project, as it came to be known, started in May ’02, and on January 14, 2003, a 15KW generator lighted up every single house in Bilgaon and the ashramshala - the boarding school which housed 300 children. Besides lighting, it also provided electricity for drawing water for drinking and irrigation, for running a grinding and oil-extracting unit, and for recreation center, during the day.

Bilgaon Project was a remarkable piece of collaboration – the project blueprint was designed by two young engineers from Kerala’s Peoples School of Energy (PSE); the special turbine was designed by a professor from Indian Instt. of Science (IISc), Bangalore; it was implemented by Mumbai-based Sarvodaya Friendship Center, four chapters of AID had provided the funding for Rs 12lacs…

…and the entire structure – the check dam, canal, tank, powerhouse - was built through the shramdaan (voluntary labour) by the village inhabitants, who owned and operated it.

More than anything, the project proved that development is possible through participation and ownership of people, through localized appropriate technological solutions, and without sacrificing people “for the greater good.”

The project became the benchmark for sustainable development, was widely quoted in the media, felicitated by the govt, and the Rural Development Minister of Maharashtra inaugurated in on the Independence Day of 2003…

This story of the Bilgaon Micro-Hydel Project was documented by Rajni Bakshi in her book “Bapu Kuti: Journeys in Rediscovery of Gandhi”. When Ashutosh Gowarikar read it, he visited the site, and it became the inspiration for the movie, Swades!

[NOTE: in 2008, I had documented this story of the Bilgaon Project, and its ironic end beyond the ‘happy ending’ in 2006, on my blog: The Un-Making of the Bollywood Movie "Swades"

…also, the cover pic is the first time I came across the existence of AID in ‘06-07 during a visit to an NGO nearby… and then kept seeing such boards in numerous remote places during the NGO site visits]

***